Francis Alÿs, Henrik Andersson, Marwa Arsanios, Monira Al Qadiri, Filipa César & Louis Henderson, Anna Dacqué, Vishal K Dar, Ingela Ihrman, Isak Hall, Louis Henderson, Susanna Jablonski, Lap-See Lam, Hiwa K, Hanni Kamaly, Britta Marakatt-Labba, Nikos Markou, Olof Marsja, Didem Pekün, Katarina Pirak Sikku, Agnieszka Polska, Raqs Media Collective, Residence-in-Nature, Neda Saeedi, Karl Sjölund, Zhou Tao, Alexandros Tzannis, Ulla Wiggen, Susanne M. Winterling, Anja Örn

17.11 2018–17.2 2019

Norrbotten, Sweden

After lying dormant for five years, Scandinavia’s first art biennial was resurrected 2018 with Emily Fahlén, Asrin Haidari and Thomas Hämén as new artistic directors. Konstfrämjandet [The People’s Movements for Art Promotion] was the initiator.

The programme was spanning over a vast geographical area with art events and exhibitions in Luleå, Boden, Jokkmokk as well as in Kiruna and Korpilombolo. 37 artists participated in, eight of which contributed especially with commissioned works. The biennial also presented performances and public artworks, and arranged film programmes. In addition, an international conference on anti-fascist organisation among activists, artists and thinkers took place towards the end of the exhibition period.

Never did they know

what the conditions afford

in the darkness of winter *

In the darkest months of the year, November through February, Sweden’s northernmost territory, Norrbotten, sees only six hours of daylight. The Luleå Biennial 2018 coincides with this period, and therefore we have taken the darkness of the region as both a necessary and generative premise for our work and thinking.

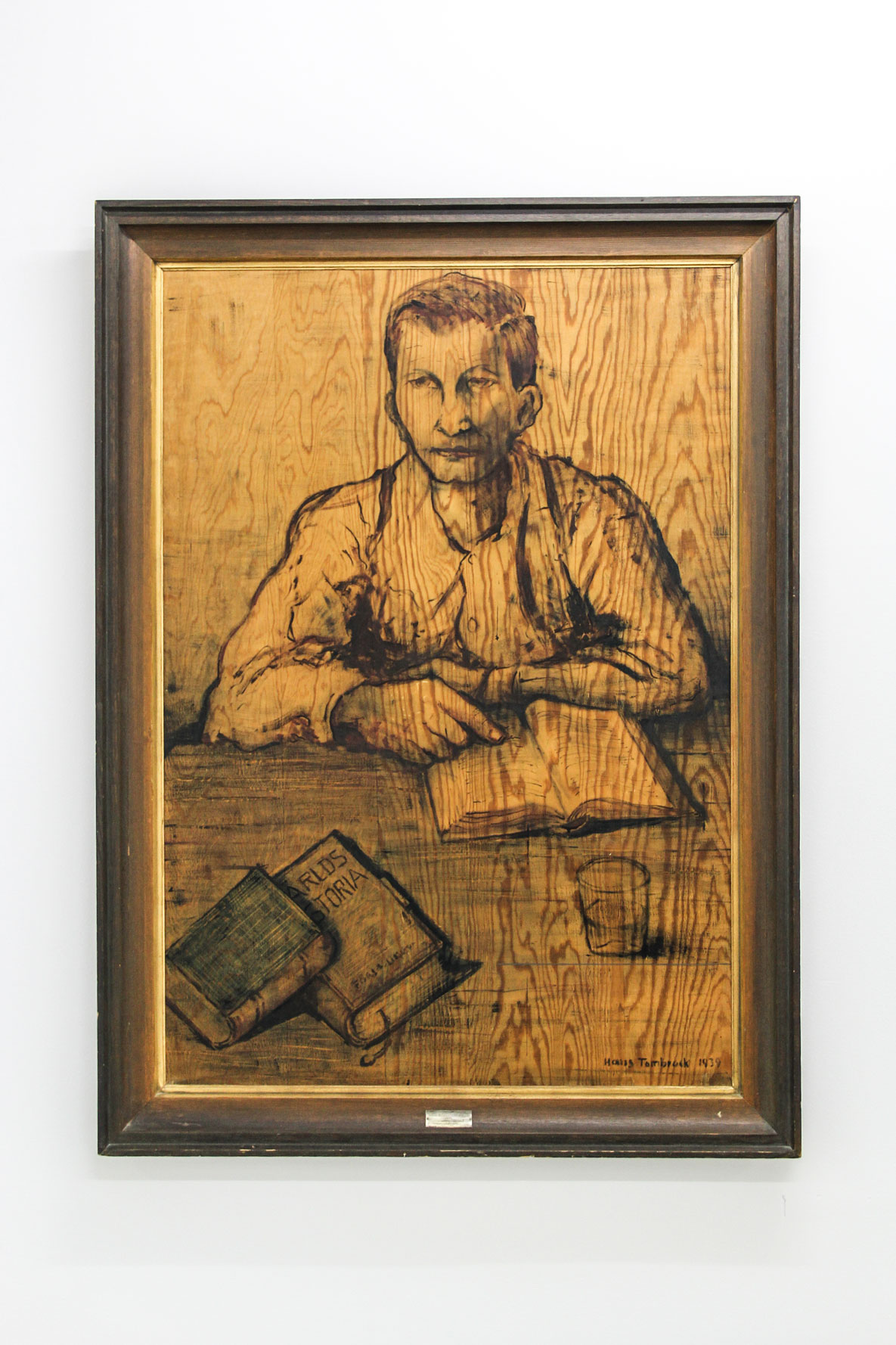

Ulla Wiggen

Agnieszka Polska

Susanne M. Winterling

Didem Pekün

Lap-See Lam

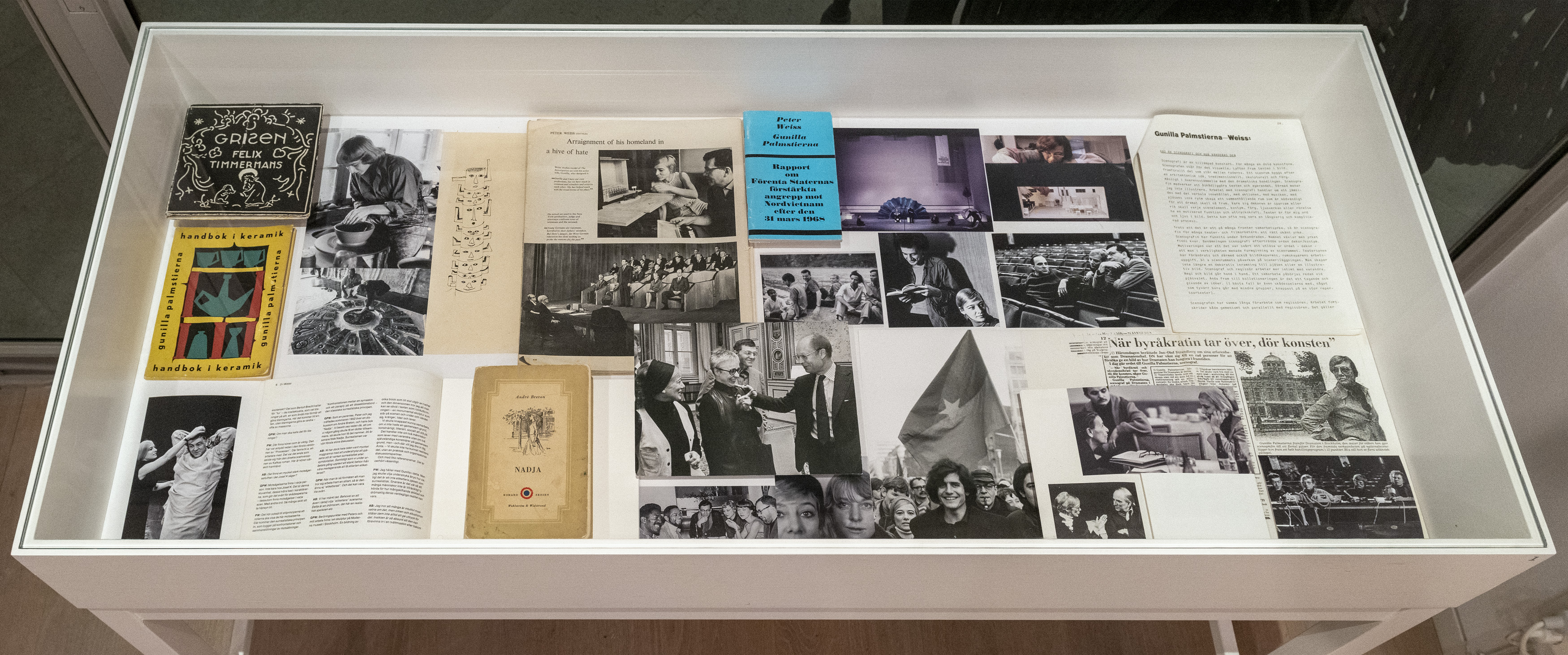

Model of Norrskensflamman used in the trial

Exhibition view at Luleå Konsthall

Anja Örn, Francis Alys

Neda Saeedi

Ulla Wiggen, Hanni Kamaly

Hanni Kamaly

Isak Hall, Hanni Kamaly

Karl Sjölund

Monira Al Qadiri, Ingela Ihrman, Susanne M. Winterling

The title of the biennial, Tidal Ground, refers to the gravitational force of the sun and moon—also known as body tide—that causes the earth’s solid surface to stir in a movement parallel to that of the oceans. Light and darkness take the place of one another in rhythmic unison with the surrounding landscape. The geographical position of Norrbotten, with its proximity to Finland and Russia, has historically made the area an active military zone. A loaded and strategic frontier from which a whole town, surrounded by five fortresses, emerged from the land to defend it against intruders. This area is rich in water, iron ore, and wood. The extraction of these resources has left deep wounds: silent rapids, gaping pits, a city collapsing into the ground. What role does darkness play in such stories?

The concept of darkness has predominantly negative connotations of fear and destruction. The biennial asks questions about what “dark times” may be said to entail: that social and political forces are also going through a period of tidal movement? Or that darkness is an ever-present condition for us to navigate? Can it, in that case, be understood as a projected space? A space that becomes one with time, where the senses are heightened and new contours may slowly become visible?

With Norrbotten’s landscape as our point of departure, and greatly inspired by its contemporary poets, a series of related exhibitions will open in Luleå, Boden, Jokkmokk, Kiruna, and Korpilombolo. Works about muted waterfalls, a fictional wilderness, and waiting for a war that fails to commence, draw parallels to similar stories in other mountains, at other riverbanks and seas. There are works that arise from particular geographies, and others that tie themselves to dreams and let go of the ground. The landscape is a stage where power and abuse play out, but also a place in which we might discover something new about ourselves. What else might we learn from the landscape, its rhythms and its tides? Can we find resistance there?

*from Linnea Axelsson’s epic poem Aednan (2018)

www.luleabiennial.se